After weeks in the leafy dark, I crawl blinking, scratched and tattered from a clump of briars – a metaphorical tangle of thorns pulling me this way and that, snagging on half-formed ideas, hazy thoughts and slow-won research. So what prompted this off-blog excursion? A fox hunt and a book, that’s what. The hunt quietly trampled over my powers of reason and the books exploded my little knowledge of war into a dangerous thing.

Hmm. No wonder it’s been quiet on the relativleyfrank front…

So – the books first: two really fascinating books about the First World War I’ve been immersed in over the past couple of months are ‘Forgotten Voices of the Somme’ by Joshua Levine and ‘To End All Wars’ by Adam Hochschild. The first is a collection of verbatim reports about various aspects of the Battle of the Somme given by men who were there, of various ranks. Yes, it is tough reading in places, but it’s also wry, surprising, touching, fatalistic, uncompromising and sometimes amusing. The second puts forward a fascinating variety of viewpoints about WW1, including those of dissenters, generals, politicians, propagandists and suffragettes.

I’d just started reading Adam Hochschild’s observations about how officers at the turn of the last century tended to come from the Cavalry, which in turn came from the moneyed classes because only they could afford the horses and kit, and were used to riding and – of course – hunting, when also I re-read TMP’s ‘A Tale – The Cleveland Fox’.

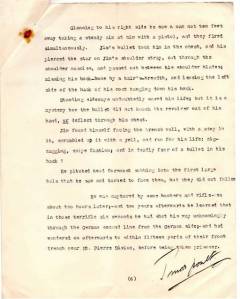

On the face of it, in the essay (written November 1922) TMP simply reports the description of an extraordinary chase by the Sinnington Hunt in the early 1880s as related by ‘The Colonel’ who had participated. The fox they flushed was reputed to have travelled to the locality around Kirkbymoorside and Sinnington from Cleveland, and to have run about twenty miles pretty much in a straight line due north in a bid to get home to safety. The essay is well written, but not really one of his best, but the essence of it is the admiration for the extraordinary feats of endurance and instinct on the part of the quarry, expressed not only by the Colonel but also by other members of the Hunt.

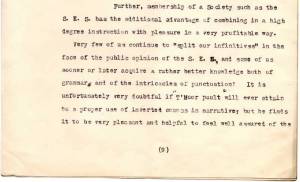

At the end of the essay, TMP’s fellow SES members enter into arguments for and against fox-hunting, which are all very familiar, even a hundred years on. I confess I don’t understand how civilised people could chase a creature to exhaustion and then allow a pack of baying hounds to tear it apart. But then I’m a soft southern suburbanite – what do I know? So I had to go and research it, didn’t I – and the first briars started catching at my sleeve.

The Sinnington Hunt, which Charles Clark Frank used to run with on foot as a boy, is a renowned Hunt of long-standing in North Yorkshire. It has a very good website at: http://www.sinningtonhunt.co.uk (sadly, though, the history doesn’t mention ‘The Old Gentleman’ Tom Parrington as Master of Foxhounds, although he was apparently quite noteworthy in the area in his time – see August 2012 archive), and seems to be thriving, in spite of the ban on hunting with dogs (or “Hounds if you please, gentlemen!” as TMP insists – followed by an explanation, of course!).

On this very good website is a thorny document called ‘Hunting, Wildlife Management and the Moral Issue’ which is a revised version of a report first published in 2009 by the Veterinary Association for Wildlife Management and the All Party Parliamentary Middle Way Group. This paper is well worth reading. It states the case for hunting with dogs, and it does so very reasonably and convincingly, particularly considering is was written by vets. Check it out (at the bottom of the webpage) at: http://www.sinningtonhunt.co.uk/17.html

By the time I’d read that document, I’d also absorbed more information about the utterly inhuman attitudes of the officers and politicians waging the war against Germany, and running cunning and sophisticated propaganda campaigns at home because they needed more troops for the Front. So I became well and truly snagged, stuck and tangled in a morass of moral brambles.

The extraordinary self-belief and pompous certitude of the chateau-dwelling generals safe behind the front line are well documented, but the sheer callousness of massively promoting patriotism and viciously stamping on pacifism at home simply in order to increase the quantity bodies to be peremptorily pulped in the bloody war machine, is shocking.

Accostomed to simply massacring peoples they perceived as inferior – for example, in the Boer War – these leaders of men were apparently unable to make the intellectual leap to even entertain the possibility that perhaps their tactics were, at best, ineffective. They simply stuck to their guns and expected the enemy to ‘play the game’. Like the instance when the Germans began to gas against the Allied army – a week prior to the gas attack a German message had been intercepted requisitioning 20,000 gas masks for German troops, but no-one had thought to act on the information. Men were just numbers.

According to his son, General Douglas Haig:

“felt it his duty to refrain from visiting the casualty clearing stations, because these visits made him physically ill.”1

A hint of humanity? Or perhaps too much harsh reality for the man who wrote:

“The nation must be taught to bear losses, … Three years of war and the loss of one-tenth of the manhood of the nation is not too great a price to pay in so great a cause.”

Hochschild records that Haig could: ‘fly into a rage when he thought British losses – and so, by association, German ones – were too low.’ And ‘Hungry Haig’ taught his subordinates well: ‘On September 30 … General Rawlinson wrote in his diary “Lawford dined. In very good form. His Division lost 11,000 casualties since July 1.”2 News of these appalling losses was filtering through to those at home. But still they came, believing that there was a ’great cause’ to fight for.

(So the briars and brambles snake and tangle – what on earth drove men to enlist in their millions? Propaganda and patriotism? But can such a double-edged sword really be enough of a prod? Could a greater spur be the fear of being thought unpatriotic? Or was the propaganda so convincing that a sense of adventure could be sufficiently stirred to make a man sign up? Are any of these really sufficient incentives?)

Remoteness was what the exalted commanders excelled in, dealing only with facts and figures. Nearer the action, but still safely behind the lines, some cavalry officers, redundant in the face of a no-man’s land filled with craters and barbed wire, held competitions, a horse show, or went fox-hunting with dogs they had brought with them to France.

Some officers, and even some troops, are recorded as revelling in what Julian Grenfell called the:

“fighting-excitement [which] vitalizes everything, every sign and word and action.”3

As a keen huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ Lord’s son, Grenfell was a good shot, and took his ‘game book’ with him when he went to fight in France. In it were entries for October 1914 of ‘105 partridges’ bagged at home, followed by ‘One Pomeranian’ on November 16 and ‘Two Pomeranians’ the next day, after a raid on a German trench.4 Julian Grenfell is celebrated as a Poet of the Great War in Westminster Abbey, for, among other work, ‘Into Battle’: http://net.lib.byu.edu/english/wwi/poets/IntoBattle.html. He was killed in action in 1915.

Will it ever be possible to truly understand why men were willing to endure the appalling conditions and sacrifices they experienced in the trenches of the First World War? The sheer complexity of this animal we call human makes it possible for the decision-makers to plot their wide objectives with intellectual detachment, then stir the blood and raise the emotions to persuade men to fight to attain them, no matter what the cost, no matter whether their efforts were effective.

Enmerging from my thorny thicket, I realise I had always believed the main characteristics of both hunting and war to be oppression and callousness, and that a sort of ‘Tally Ho!’ mentality prevailed among the generals due to their privileged backgrounds. Now, although a few snags remain, I am certain that the oppression and callousness are solely attributable to those who plan and wage war. Politicians and commanders who commit men to kill each other for one ‘great cause’ or another, seem to deny their humanity to the point of blindness, rigidly sticking to their decisions, and damn the consequences, so long as their objectives (which are not always obvious or great) are achieved. Apparently, few peace negotiations were undertaken during the First World War, and both sides assumed that it would be over within months of starting, even as it continued and the human cost grew. Besides, God was on the side of the righteous.

As far as hunting goes, everything’s a lot clearer. During a chase, the fox, a ‘quarry species’ brings all its instincts to bear to evade the hounds, and does not experience fear in the manner attributed to it by humans, who do. Hounds are a ‘scenting and tracking’ species, and if a hound finds its quarry, the kill is instant, so no fox escapes to die slowly of injuries. Both animals do what comes naturally, and before hunting with dogs was banned in 2005, humans on horseback usually followed them, appreciating the thrill of the chase and admiring the tactics of the fox – and only one in six foxes were killed during any season.

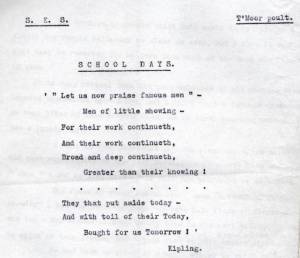

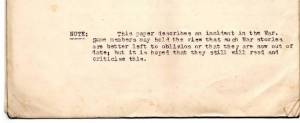

Exrtacts from ‘A Tale – The Cleveland Fox’ written in 1922:

References

1 P210, To End All Wars, Adam Hochschild

2 p209, To End All Wars, Adam Hochschild

3, 4 p126, To End All Wars, Adam Hochschild